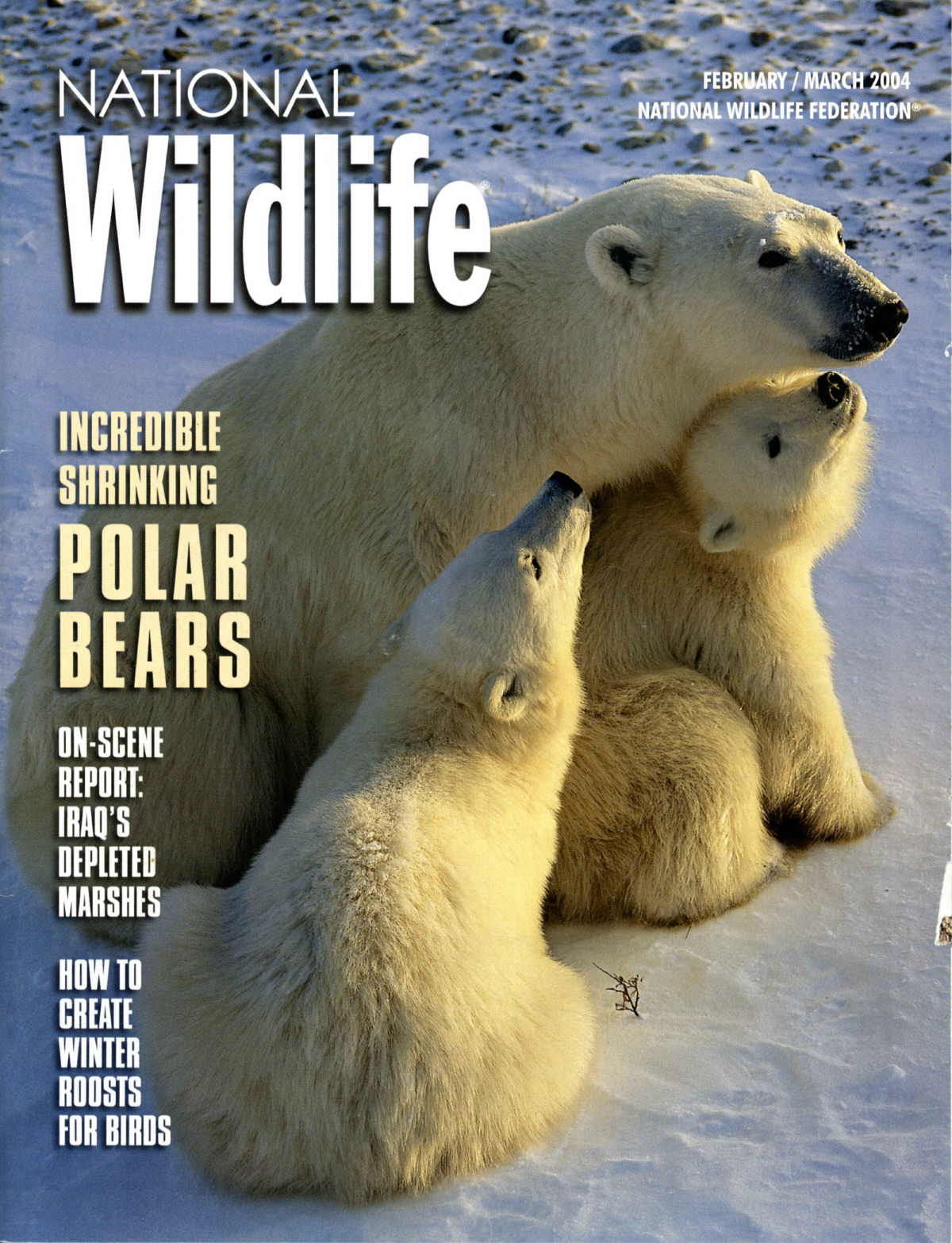

By March when a mother polar bear departs her earthen den with nursing cubs into subzero temperatures along Canada's Hudson Bay, she's fasted for eight months, dropping more than half her weight, as much as 400 pounds.

Fortunately, her emergence onto the sea ice along the continental shelf coincides with the birth of ringed seals, her primary prey.

From April until the ice breaks up in the summer and the seals disappear into open water, she is in a desperate race to pack on pounds of fat to get her through the long summer and fall fast. If she becomes too lean, she’ll stop producing milk and her cubs will die.

Hunting is hard work. With her massive limbs and 12-inch-wide paws evolved for prowling the ice and swimming, she expends twice the energy to walk than most other mammals. So she stalks her prey slowly, relying on her extraordinary sense of smell -- she can sniff seals in their subnivean lairs two miles away. Often, she'll rely on still hunting, remaining motionless on her stomach for long minutes by a lead or breathing hole, waiting for a seal to surface.

Polar bears, the largest carnivores in the world, abandoned the land for this harsh life between 100,000 and 200,000 years ago. They’ve adapted perfectly. Their hair is clear, not white, a hollow prism that reflects light and provides camouflage. Their skin is black to absorb heat. A layer of blubber inches thick keeps them warm.

Taxonomists named them Ursus maritimus, the bear of the sea. They have been known to swim as far as 60 miles in a day. But they're really the bear of the ice. The shifting floes of the Arctic are home.

Now, the ice in the western Hudson Bay is abandoning them, threatening their long-term survival. It’s a preview of the challenges other bear populations farther north will face in the coming decades.

Global warming is causing the ice pack to melt an average of two weeks earlier each July. The timing couldn't be worse for polar bears, especially pregnant and nursing females and their cubs. Ringed seal pups wean in May and emerge from their lair, a polar bear delicacy that is 50 percent fat and still ignorant of predators. Adult seals haul out on the ice to molt in June, offering bears a second course. When the ice disappears early, so does the bears’ larded buffet.

"Nobody really knows what percentage of fat a bear stores and uses through the year is captured in the spring," says Ian Stirling, a Canadian Wildlife Service scientist who has studied polar bears for more than 30 years. "It's certainly well over 50 percent and may be as high as 70 or 75 percent. All we know is its terribly important."

What Stirling and his colleagues do know is that bears along the Hudson Bay are lighter and in poorer condition than they were 20 years ago. For each week the ice breaks up earlier, the bears come ashore 22 pounds lighter. Overall, bears on average weigh about 180 pounds less than they did in 1985.

Climate models predict the area will be three to five degrees warmer within 50 years. With every degree increase, the ice breakup will happen one week earlier.

The 1,200 bears of the western Hudson Bay are at the southernmost extreme of their range. So as the world continues to warm, what happens there will happen farther north to the rest of the estimated 25,000 bears in 20 distinct circumpolar populations. Already, ice conditions in the Beaufort Sea off the north coast of Alaska, home to another major polar bear population, are changing dramatically.

The longer summers on the Hudson Bay are particularly challenging for pregnant and nursing females and their cubs. Mothers weigh between 220 to 400 pounds after leaving the den and need to gain between 100 and 200 pounds before the thaw arrives. Healthy pregnant females often gain more than 400 pounds. So a mother spends half her time hunting, catching a seal every four or five days. She can gorge on more than 60 pounds of seal meat at a single sitting, often delicately using her incisors to strip away just the fat (a typical 1,200 pound male can down 150 pounds at a time). Then she takes a nap, digging a pit on the lee side of a pressure ridge.

Polar bear cubs do not wean until their second or third year. Less than half of those born live to become adults. The main cause of death is a lack of food. When mothers become too lean, they simply stop nursing and abandon their cubs.

"Lighter cubs have lower survival rates and light cubs come from leaner pregnant females," says Andrew Derocher, who has studied bears for 20 years. "For a polar bear, fat is where it's at."

In recent years, hungry bears foraging for food have become a nuisance at the dump in nearby Churchill, Manitoba. The town has 23 cinderblock cells to house intruding bears until the bay freezes and they can be airlifted north. (Males, which average about 1,200 pounds, begin hunting again in November when the ice returns.)

Churchill bills itself as “The Polar Bear Capital of the World” and relies on tourism to drive the local economy. That economy may be headed for tough times.

"If the ice goes in Hudson Bay completely, which is forecast to happen at some time, then there won't be any polar bears there," Stirling adds. "And there's no place they can go. People often say. 'Can't they just go farther north?' The answer to that is no because that habitat is already occupied by other polar bears."

Derocher adds that while some bears do cross the North Pole, the conditions there are so extreme that it is inhospitable, even for them.

Stirling and other researchers say polar bears are in no immediate danger of extinction. However, they note that environmental change over time is not linear, nor is it easy to predict.

"For the long term, I think it looks very bad for polar bears," Stirling says. "Certainly, they will be gone in the southern portion of their range."

Derocher, a researcher with the University of Alberta, returned recently from six years studying polar bears on Norway's Svalbard archipelago. He thinks bears are particularly vulnerable to the effects of global warming. They're highly specialized, adapted to life on the ice. They reproduce slowly. And as they shift farther north away from the continental shelf, there is less for them to eat.

"We're likely to see very large changes in their distribution, changes in their ecology and certainly changes in the number of bears that the planet is able to support," he adds.

Both men say as long as there is ice, there will be bears. But they add an ominous coda: "If the ice goes," Stirling says, "the bears will go."

The connection between global warming and the bears’ deteriorating condition could be proven only because of Stirling’s determination to build a unique database about the lives of polar bears – and a bit of lucky geography.

The Hudson Bay bears are the most studied population in the world, thanks to their relatively easy accessibility and Stirling's stubborn begging for funding year after year. Other populations move across large expanses of moving ice. Along the bay, the entire population comes ashore in one concentrated area for a few months annually.

That makes working there efficient, a necessity for cash-strapped researchers. They track bears by helicopter and dart them with an immobilizing drug named Telazol, know they won’t have to survey barren stretches of ice looking for their subjects. Typically, they capture about 150 bears each September ashore along the western Hudson Bay. Over three decades, Stirling and his associates have made roughly 5,000 captures. Eighty percent of the adult bears in the area have been tagged, tattooed, weighed and measured, had blood drawn and their teeth inspected, many more than once. Each is checked for fat and given a subjective rating from one to five, with five being what Stirling calls "a big tub of jelly with little, stubby legs."

The luck came in the location. As it happens, the western Hudson Bay has been a hot spot, more affected by global warming than nearby areas so the changes have been more dramatic there. While the world generally is getting warmer, temperature changes vary by location; southeastern Hudson Bay, for example, has actually gotten cooler.

In the early 1980s, Stirling began noticing that bears seemed lighter. Cubs were taking longer to wean so females were reproducing less frequently. There was no Eureka moment, he says, just a gradual realization and a lot of work on the ice.

He got another clue after Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines blew its top in 1991 and the sulphuric acid particles it sent into the atmosphere cooled the planet. The following summer the ice on Hudson Bay melted almost a month later, extending the bears’ hunting season. The effect was dramatic. The bears were heavier, had more cubs and more of them survived those brutal first years. But that was still only a piece of a tricky, subtle puzzle.

"It took 20 years to have enough data to determine that this was happening," Stirling says. "There is quite a bit of annual fluctuation. You can't detect these kinds of things unless you've been able to look at it for a good, long time."

Researchers point out that polar bears are at the top of the food chain. They’re representative of stress facing the entire ecosystem caused by climate change. "Being able to use the polar bear as a vehicle for looking downward into how the while arctic marine ecosystem works is an extremely interesting way of going about it, " Stirling says. That's what has fascinated him all these years.

He's cautious about making predictions. "Usually when you take large predators out of an ecosystem you get major changes. Exactly what those would be I don't think anybody would say," he adds. "But look at some of the recent literature on the effects of the removal of sharks and large fin fishes from the marine ecosystem. Clearly, there would be huge changes (in the Arctic ecosystem)."

Studying bears is expensive and difficult. "Funding," Stirling says, "has gotten harder and it continues to get more difficult." He spends 20 percent of his time tracking down money to keep the program running.

Derocher wants to put satellite telemetry collars on ten bears a year so he can follow them for long periods of time and create a database on how individuals fare from year to year. But the cost is $7,000 per bear annually. Add in the helicopter and the project budget is more than $100,000, a fortune for a polar bear researcher. "There's nothing cheap about polar bears," he says, chuckling.

It's dangerous, too. Bears can kill with one swipe of a paw. Derocher carries a loaded pistol on the ice, though he's never used it.

Stirling is nearing retirement age and says it's time for some of the younger researchers to step up. In Derocher and Nick Lunn, his colleague at the Canadian Wildlife Service, he has too eager disciples. Lunn, 43, is determined to carry on his work on the Hudson Bay bears. "There's no other database like this on any arctic species," Lunn says. "If you let it go, even for a year, it's gone. You can't fill that gap."

Derocher plans to study climate change and the effect on bears populations. "I believe a better understanding of interactions between sea ice, polar bears and their prey are the key issues for understanding how polar bears will respond to climate change over the coming years," he says, adding that -- if there's funding -- he hopes to continue investigating the effects of toxic chemicals (see sidebar).

Derocher spends a lot of his time thinking about what it's like to be a polar bear, walking on the sea ice, using smell to find dinner during the howling Arctic night when it is minus 40 degrees. "It's a scenario that humans don't relate to very well," he adds. "You can't help but respect an animal making a living in this kind of environment."

Lunn, meanwhile, wants to study individuals, especially their reproduction. "It may be that every bear is not affected in the same way" by the warming trend, he says. And, in that, there may be hope for the bears of the Hudson Bay.

SIDEBAR

In Svalbard, Derocher found another challenge facing the bears: pollution. Toxic chemicals, including flame retardants, PCBs and pesticides such as DDT, repeatedly evaporate, rise and then fall to the ground, leapfrogging across the globe. Eventually, they ride northbound winds, migrating to the Arctic Circle. Though many of the toxins were banned decades ago, they remain in the arctic, building up in ice and ocean sediment.

Over time, they accumulate in the fat of animals, especially predators at the top of the food chain. For instance, high levels of PCBs have been found in orcas, seals, bottlenose dolphins and belugas as well as Svalbard's polar bears. The levels in bears are much higher in Svalbard as a result of nearby Russian pollution, than they are in the western Hudson Bay.

Researchers also suggest that there may be increased mortality among small cubs that receive pollution through their mother’s milk. Levels of testosterone, progesterone, vitamin A and thyroid hormones, important for a wide range of biological functions, are reduced in bears with high levels of pollutants in their blood.

Derocher determined that Svalbard bears with elevated levels of contaminants suffered from compromised immune systems. As a result, he theorizes that bears in the area took longer to recover from over harvesting after hunting was banned in 1973 than they otherwise would have. He believes pollution levels in bears are dropping, but remains concerned.

"It's a good news, bad news story," he says. "The good news is we seem to be better at reducing these things. The bad news is we're not 100 percent efficient at doing that. So the offshoot is we are looking at some long-term effects. But at this time it's really hard to quantify what those are."

---END-----

|

Jim Morrison

Jim Morrison

Travel

Travel

Culture

Culture

Sports

Sports

Environment

Environment

Business

Business

Bio

Bio

Photos

Photos

Links

Links

Contact

Contact

Blog

Blog

Travel

Travel Culture

Culture Sports

Sports Environment

Environment Business

Business Bio

Bio Photos

Photos Links

Links Contact

Contact Blog

Blog

Travel

Travel Culture

Culture Sports

Sports Environment

Environment Business

Business Bio

Bio Photos

Photos Links

Links Contact

Contact Blog

Blog